Stay updated on what is trending in health. Discover tips and resources for a healthier, balanced life.

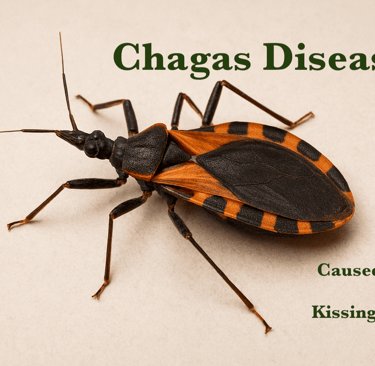

Chagas Disease Unveiled: Kissing Bug Secrets Revealed

Discover Chagas disease: caused by the kissing bug's bite, spread by Trypanosoma cruzi. Learn symptoms, risks, prevention tips, and more in this helpful guide!

DISEASES AND CONDITIONS

Dr. S. Ali

9/10/20256 min read

When people think of tropical diseases, malaria or dengue might come to mind. But there’s another illness that affects millions, often quietly, and it’s called Chagas disease. Let’s break it down in a simple way.

What is Chagas disease?

Chagas disease is caused by a parasite called Trypanosoma cruzi. You usually get it from the bite of a bug called the “kissing bug” (also known as the triatomine bug). These bugs are common in parts of Latin America, where the disease is most widespread.

So, what’s this bug like?

The kissing bug (Triatomine bug) is about the size of a fingernail, ranging from 0.5 to 1 inch long, with a flattened, oval shape. Their color varies—brown, black, or reddish-brown—often with distinctive yellow, red, or orange stripes on their bodies.

Triatomine bugs are nocturnal insects — they come out at night and feed on blood, kind of like mosquitoes. Unlike mosquitoes, though, they don’t just buzz around in the open. They usually hide during the day in cracks, thatched roofs, or piles of wood and leaves, and come out at night to feed.

They can fly, but they’re not strong fliers. Most of the time they crawl on walls, ceilings, or beds to reach people while they’re asleep. They’re called “kissing bugs” because they often bite around the lips and face — warm areas with thinner skin.

The bug itself isn’t the real danger — it’s their droppings. After feeding, they often leave parasite-containing feces near the bite wound. If that parasite gets rubbed into the skin, eyes, or mouth, infection can happen.

The tricky part? Many people with Chagas don’t even know they have it. Symptoms can be very mild—or not show up at all—for years.

Who’s at Risk?

You might think this is just a “somewhere else” problem, but it’s closer than you think. About 6 to 8 million people globally have Chagas, with many cases in rural areas of Mexico, Central, and South America. But with folks moving around, it’s showing up in places like the U.S. and Europe too. It can hit anyone who crosses paths with an infected bug or contaminated blood. If you’ve lived in or visited endemic areas, or have family from there, it’s worth paying attention.

How do you catch it?

The kissing bug bites, usually at night, often around the face or lips (that’s why it’s nicknamed the “kissing bug”). After biting, the bug may leave droppings that contain the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.

The kissing bug bite itself doesn’t give you Chagas disease. The problem happens when the bug leaves droppings near the bite. Those droppings contain the parasite (Trypanosoma cruzi). If the droppings accidentally get rubbed into the bite wound, or into your eyes, mouth, or any small cut, the parasite can enter your body.

In other words, it’s not normal touching of your eyes or mouth or the bite itself that spreads Chagas. The risk comes specifically from contact with infected bug droppings.

But that’s not the only way. Chagas disease can also spread through:

Blood transfusions: If donated blood isn’t carefully screened, the parasite can be passed from one person to another. This used to be a bigger problem in Latin America before widespread screening programs were put in place.

Organ transplants: A donated organ from someone with the parasite can transmit the infection to the recipient.

Eating contaminated food or drink: In rare cases, food or beverages that have been contaminated with the kissing bug’s droppings can carry the parasite and infect people who eat or drink them.

From mother to baby during pregnancy: A pregnant woman with Chagas can pass the parasite to her baby before birth.

Symptoms: What to watch for

Chagas disease has two main phases:

Acute phase (right after infection): This stage usually lasts for the first few weeks or months. Symptoms are often mild, so people may not realize they’re infected. You might notice fever, fatigue, swollen eyelids (called Romaña’s sign), body aches, or sometimes a rash or swollen lymph nodes. Because these signs look like many other common illnesses, it’s easy to miss. Most people recover from this phase and think it’s over — but the parasite often stays hidden in the body.

After the acute phase, many people enter a period where they feel completely healthy and have no symptoms at all. This stage can last for years, even decades. However, the parasite is still present in the body, slowly working in the background. This is why regular check-ups are important if you’ve ever been at risk.

Chronic phase (years later): This is where things become more dangerous. Even if you feel fine for years, the parasite can slowly damage the heart and digestive system. Some people develop heart problems like heart failure, irregular rhythms, or sudden cardiac arrest. Others may have digestive issues such as difficulty swallowing, severe constipation, or an enlarged esophagus or colon. Not everyone develops these complications, but for those who do, they can be life-threatening.

The Hidden Dangers

Here’s where it gets serious. For most, the chronic phase is silent—no symptoms for years. But for about 20-30% of people, it can lead to big issues like an enlarged heart (which can fail), irregular heartbeats, or even digestive troubles like a swollen colon. These complications can creep up 10-30 years later, which is why catching it early is a game-changer. And yes, it can be life-threatening if ignored, especially for older adults or those already unwell.

Can Chagas disease be treated?

Yes, but treatment works best if it’s started early. Doctors may prescribe antiparasitic medications, such as benznidazole or nifurtimox. These drugs help kill the parasite and are especially effective in children and young adults, preventing the infection from progressing. The earlier treatment begins, the better the chances of avoiding long-term damage.

For people with long-term (chronic) Chagas disease, treatment often shifts toward managing complications. For example, doctors may use medications, pacemakers, or even surgery to help with heart problems caused by the disease. If the digestive system is affected, patients may need special diets, procedures, or in severe cases, surgery to improve swallowing or bowel function.

Even in chronic cases, starting treatment can sometimes slow down the disease and improve quality of life — so it’s worth discussing options with a doctor if you think you’ve been exposed.

Can you prevent Chagas disease?

Absolutely. Prevention is mainly about avoiding contact with the kissing bug and reducing risk factors:

Use insect screens on windows and doors: This simple step helps keep kissing bugs from entering your home at night when they are most active. Make sure screens are well-fitted and without holes.

Keep houses clean and reduce places where bugs can hide (like cracks in walls): Kissing bugs love dark, sheltered spots. Sealing up cracks in walls, repairing roofs, and keeping clutter away reduces their hiding spaces. A clean, well-maintained home makes it harder for them to settle in.

Avoid sleeping in areas known to be infested: In rural parts of Central and South America, where Chagas is most common, people are at greater risk if they sleep in mud or thatched houses. If you’re traveling in these regions, choose lodging with good construction and screened sleeping areas.

Screen blood and organ donors (which is now standard in many countries): Because the parasite can spread through transfusions and transplants, most countries with Chagas risk now screen donors carefully. This extra step has greatly reduced cases passed through medical procedures.

Why should you care?

Chagas is often called a “neglected tropical disease,” which means it doesn’t get the funding or awareness it needs. But with global travel, it’s not just a far-off concern anymore. Raising awareness—talking about it, learning the signs—can push for better screening and treatment everywhere. Plus, it’s a reminder to support health initiatives in affected regions, where poverty and poor housing make it harder to fight back.

So, next time you hear about kissing bugs or see a weird bug bite, maybe think twice! Keeping an eye out, protecting yourself, and spreading the word can make a difference. Have you ever encountered something like this, or know someone who has? Let’s keep the conversation going—your curiosity could help someone stay healthy!

Bottom line

Chagas disease is often called a “silent killer” because it can hide in the body for years before showing serious symptoms. The good news? It’s preventable, and treatment is available if caught early.

If you’ve lived in or traveled to an area where kissing bugs are common, and you’ve had unusual symptoms or heart problems, it’s worth asking your doctor about testing.

Remember: Knowing the risks, symptoms, and prevention steps can protect not just you, but also your family.

Sources:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/index.html

World Health Organization (WHO)

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis)

Mayo Clinic

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chagas-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20356212

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)

https://www.paho.org/en/topics/chagas-disease

Pulse Your Health

Empowering you to achieve your health goals.

Contact

© 2026. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer: The content on this website is for informational purposes only and is not medical advice. Always seek the advice of your physician or other suitably qualified healthcare professional for diagnosis, treatment and your health related needs.